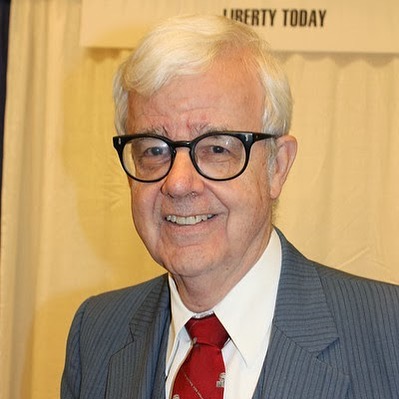

Robert B. “Bob” Ekelund passed away on August 17, 2023, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease and other illnesses. A professor of economics at Auburn University for three decades, he was a prolific scholar and an admired professor. His energy, curiosity, and intellect could not be satiated by the mere challenges of a career as an academic economist, and his appetite for learning extended into music and the arts as well.

Robert B. Ekelund (1940-2023)

As a scholar, Prof. Ekelund’s interests were wide-ranging. In a time of hyper-specialized quantitative economics, he was a generalist capable of writing with lucidity and force on many different topics. He was extraordinarily productive, writing over 200 academic papers and more than two dozen books. Among his books are The Economics of American Art: Issues, Artists, and Market Institutions, coauthored with John D. Jackson and Robert Tollison; The Marketplace of Christianity, coauthored with Robert Hébert and Robert Tollison; Tariffs, Blockades, and Inflation: The Economics of the Civil War, coauthored with Mark Thornton; Sacred Trust: The Medieval Church as an Economic Firm, coauthored with Gary Anderson, Audrey Davidson, Robert Hébert, and Robert Tollison; and several economics textbooks. Notable among Prof. Ekelund’s textbooks is the number one history of economic thought textbook available today, A History of Economic Theory and Method, coauthored with Bob Hébert. Most recently, his 2022 book with Phil Gramm and John Early, The Myth of American Inequality, revealed the misuse of economic statistics in policy. The diversity of his interests is plain to see.

As a professor, Ekelund managed to confer not only his knowledge, but his inquisitiveness as well, on countless students. He directed over 50 doctoral dissertations and many master’s theses. While I was a graduate student at Auburn, I wrote my dissertation under Andy Barnett’s supervision, but I have good memories of Prof. Ekelund’s teaching. I still remember the mischievous twinkle in his eye as he asked me a simple, incisive question that undermined an argument I had been making involving inheritance laws. I was forced to shore up my reasoning–which was of course his purpose. Prof. Ekelund had good advice on how to navigate the academic world as well. When I stopped by his office to tell him I had taken on a contract writing project to ease the financial strain of graduate school, he listened patiently, but I could tell he was disappointed. “That’s not economics,” he said. Graduate school was not the time to stray from the main objectives: learn economics and finish the degree. I continued with the writing project, but kept the lesson in mind when I reached the dissertation stage. By minimizing distractions and other work, I was able to finish on schedule and avoid the dreaded long-term ABD (all but dissertation).

In the decades since, I saw him from time to time when I would return to Auburn for Mises Institute events. He was always gracious in his conversations with me, and I appreciated his wit and sincerity. He seemed genuinely interested in my career, and indeed he kept up with many of his former students (here is another remembrance from a friend who was also in my cohort at Auburn University).

I remember Prof. Ekelund best as a scholar and professor, but he was also an accomplished classical pianist, artist, gardener, and gourmet. He recorded several CDs, and was a talented painter. Earlier this year, my wife and I were in Taos, New Mexico, the source of inspiration for many of Ekelund’s paintings, and I thought of him as we wandered through several of the art galleries there. We selected a plein air landscape of distant mountains from a local artist, and I wondered if my former professor would approve of the choice. I suppose that is the mark of a good teacher–the student continues to evaluate his own decisions in light of his teacher’s example.

Bob Ekelund’s passing is a loss to us all. But his work, and remembrances of his zest for life, remain behind so that we can all continue to learn from him.