One of my lectures at Mises University each summer concerns environmental issues. I make changes every year, but I always mention Murray Rothbard’s essay “Law, Property Rights, and Air Pollution.” In it, Rothbard lays out a libertarian method for handling what mainstream economists usually call externalities—the side effects of production or consumption activity on bystanders. The contrast between Rothbard’s welfare economics and the mainstream is plainly visible. Whereas many mainstream economists try to measure costs and benefits of pollution in order to come up with the most efficient level of pollution, or the appropriate tax to impose on the polluter (a la A.C. Pigou), Rothbard strictly eschews any such effort to measure the immeasurable.

Emissions Taxes and Tradable Permits

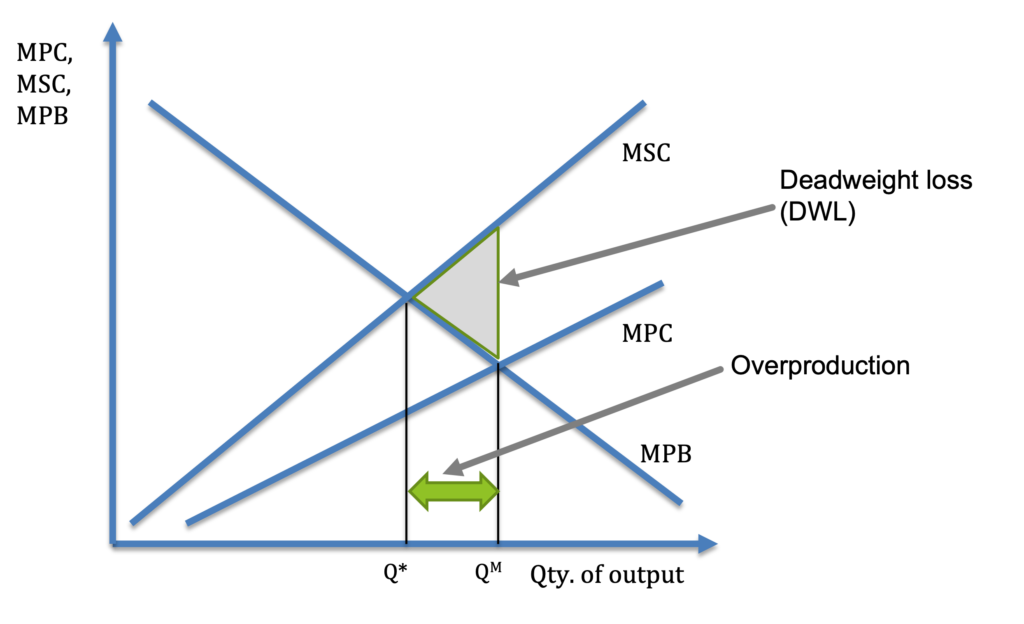

The typical presentation of negative externalities involves something like the diagram below, where the costs on bystanders are added to the marginal private costs (MPC) faced by the polluting firm, to come up with a marginal social cost (MSC) that, along with the marginal private benefit (MPB) to the firm from producing its output reveals the ideal level of output. In the presence of these negative externalities, and absent positive externalities that would offset these, the market level of production QM is too high, compared to the welfare-maximizing level of production Q*.

As court-made law to settle conflicts over nuisances like pollution has been increasingly regarded as inadequate to deal with externalities, government interventions have typically taken three forms: 1) command-and-control regulation, 2) emissions taxes, or 3) cap-and-trade systems.

Continue reading “Subjective Value and Externalities”